Defeating Code Obfuscation with Angr

A few weeks back I encountered an obfuscated piece of code. Reversing it seemed very tedious.

Today I’ll go into detail on how I tackled it by using “Angr”, a suite of Python3 libraries that lets you load a binary and do a lot of cool things to it. You can read more about it here.

This blog post will cover practical guidelines on how you can use Angr in order to reverse engineer obfuscated code.

Table of Contents

Introduction

I’ll be giving a short introduction to Angr as I believe that knowing how our tools work is important. If you don’t care for that (or already know about Angr) feel free to skip ahead to the reversing part.

Symbolic Execution - Short Introduction

As I mentioned, Angr is a suite of Python libs and I’m using it as a framework for binary analysis. Angr works by combining static and dynamic symbolic analysis, which is called “concolic” analysis. Nonetheless, people usually refer to it as a symbolic execution/analysis engine.

What is symbolic execution you ask? Well, that could be a blog post by itself (if not a book). But let me try to simplify it real quick.

Symbolic execution involves simulating the execution of a program by replacing input values of a program with “symbolic” values. As the simulation of the execution progresses constraints are added to “symbolic” values whenever the input is processed. When a branch condition is encountered, the simulation is forked into two paths: one path where the branch condition evaluates to true and the other where it evaluates to false.

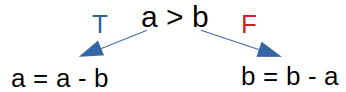

In layman terms, input values are replaced by symbolic ones. Then, executing the program with symbolic values builds up constraints. Have a look at this simple if statement:

// Assume a & b are controlled by the user

if (a > b)

a = a - b;

else b = b - a;

Graph view:

Meaning, the constraints for the left branch is a>b, while the constraints for the right branch is a<=b.

Real-world programs aren’t as simple, and the constraints for branches deep in the code can get very big, very fast. In order to solve these constraints Angr uses Z3, a theorem prover by Microsoft. Z3 checks if the constraints are satisfiable (SAT) or not. Assuming a certain branch has satisfiable constraints, we can ask Angr to give an example for an input that meet the constraints.

Angr - Basic Usage

Showcasing basic usage of Angr. In the following example we’ll add constraints and ask Angr to evaluate (solve) them.

Consider the following code snippet:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

void main(int argc, char *argv[]){

int a=atoi(argv[1]);

int b=atoi(argv[2]);

if (10 > a && a > 5 && 10 > b && b > 1 && 2*b - a == 10)

{

printf("[+] Math is hard... but not 4 u! \n");

}

}

We’ll use Angr to add the constraints manually, and then solve it by using the built-in solver. This is different from how we usually use Angr and it’s only meant to show case a bit before diving into a complicated case.

Step-by-step iPython commands with explanations:

# Importing angr

In [1]: import angr

# A wrapper for Z3. Claripy is used for constraint-solving.

In [2]: import claripy

# Loading the binary to angr.

In [3]: p = angr.Project('./a.out')

WARNING | 2021-05-24 17:54:05,450 | cle.loader | The main binary is a position-independent executable. It is being loaded with a base address of 0x400000.

# Constructs a state ready to execute at the binary's entry point.

In [4]: state = p.factory.entry_state()

# Create a bitvector symbol named "a" of length 32 bits

In [5]: a = state.solver.BVS("a", 32)

# Create a bitvector symbol named "b" of length 32 bits

In [6]: b = state.solver.BVS("b", 32)

''' Adding constraints manually '''

In [7]: state.solver.add(10>a)

Out[7]: [<Bool a_39_32 < 0xa>]

In [8]: state.solver.add(a>5)

Out[8]: [<Bool a_39_32 > 0x5>]

In [9]: state.solver.add(b>1)

Out[9]: [<Bool b_40_32 > 0x1>]

In [10]: state.solver.add(b<10)

Out[10]: [<Bool b_40_32 < 0xa>]

In [11]: state.solver.add(2*b - a == 10)

Out[11]: [<Bool 0x2 * b_40_32 - a_39_32 == 0xa>]

# Evaluates the value of "a" by taking the current constraints into consideration.

In [12]: state.solver.eval(a)

Out[12]: 6

# Evaluates the value of "b" by taking the current constraints into consideration.

In [13]: state.solver.eval(b)

Out[13]: 8

Now that we got the basics down, let’s move over to the main event.

Reversing Obfuscated Binary

The obfuscated binary that I originally had to work on cannot be disclosed at this time. Therefore, I’ll be showcasing a very similar use case. Do not be discouraged though, as the fundamentals are exactly the same.

The binary that we’ll be reversing is “Jack” from DarkCTF2020.

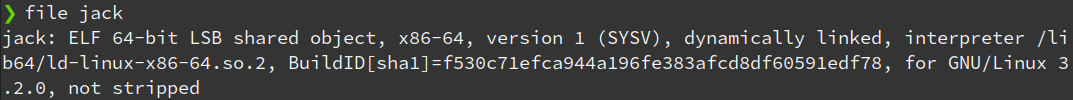

File Analysis

Starting with basic utilities to gather information about the binary.

Making the file executable & using ltrace to trace the library functions:

This yields us some good information on what we’re up against.

It seems that the challenge is to find the ‘key’ for the program (There may be more than one).

Next, I decided to load the binary in Ghidra in order to take a better look at what’s going on.

Decompiling the main program:

bool main(void)

{

uint uVar1;

size_t sVar2;

long in_FS_OFFSET;

uint local_38;

int local_34;

int local_30;

int local_2c;

char local_28;

char local_27;

char local_26;

char local_25;

char local_24;

char local_23;

char local_22;

char local_21;

char local_20;

char local_1f;

char local_1e;

char local_1d;

char local_1c;

char local_1b;

char local_1a;

char local_19;

undefined local_18;

long local_10;

local_10 = *(long *)(in_FS_OFFSET + 0x28);

puts("Enter your key: ");

fgets(&local_28,0x11,stdin);

local_18 = 0;

sVar2 = strlen(&local_28);

if (sVar2 != 0x10) {

puts("Try Harder");

}

else {

local_38 = local_25 * 0x1000000 + (int)local_28 + local_27 * 0x100 + local_26 * 0x10000;

local_38 = local_38 ^ ((int)local_38 >> 3 & 0x20000000U) + local_38 * 0x20;

local_38 = local_38 ^ local_38 << 7;

local_38 = (local_38 >> 1 & 0xff) + local_38;

local_38 = ((int)local_38 >> 3 & 0x20000000U) + local_38 * 0x20 ^ local_38;

local_38 = local_38 ^ local_38 << 7;

local_38 = local_38 + (local_38 >> 1 & 0xff);

uVar1 = local_21 * 0x1000000 + (int)local_24 + local_23 * 0x100 + local_22 * 0x10000;

uVar1 = uVar1 ^ ((int)uVar1 >> 3 & 0x20000000U) + uVar1 * 0x20;

uVar1 = uVar1 ^ uVar1 << 7;

uVar1 = (uVar1 >> 1 & 0xff) + uVar1;

uVar1 = ((int)uVar1 >> 3 & 0x20000000U) + uVar1 * 0x20 ^ uVar1;

uVar1 = uVar1 ^ uVar1 << 7;

local_34 = uVar1 + (uVar1 >> 1 & 0xff);

uVar1 = local_1d * 0x1000000 + (int)local_20 + local_1f * 0x100 + local_1e * 0x10000;

uVar1 = uVar1 ^ ((int)uVar1 >> 3 & 0x20000000U) + uVar1 * 0x20;

uVar1 = uVar1 ^ uVar1 << 7;

uVar1 = (uVar1 >> 1 & 0xff) + uVar1;

uVar1 = ((int)uVar1 >> 3 & 0x20000000U) + uVar1 * 0x20 ^ uVar1;

uVar1 = uVar1 ^ uVar1 << 7;

local_30 = uVar1 + (uVar1 >> 1 & 0xff);

uVar1 = local_19 * 0x1000000 + (int)local_1c + local_1b * 0x100 + local_1a * 0x10000;

uVar1 = uVar1 ^ ((int)uVar1 >> 3 & 0x20000000U) + uVar1 * 0x20;

uVar1 = uVar1 ^ uVar1 << 7;

uVar1 = (uVar1 >> 1 & 0xff) + uVar1;

uVar1 = ((int)uVar1 >> 3 & 0x20000000U) + uVar1 * 0x20 ^ uVar1;

uVar1 = uVar1 ^ uVar1 << 7;

local_2c = uVar1 + (uVar1 >> 1 & 0xff);

check_flag(&local_38);

}

if (local_10 == *(long *)(in_FS_OFFSET + 0x28)) {

return sVar2 != 0x10;

}

/* WARNING: Subroutine does not return */

__stack_chk_fail();

}

We can see that there is a check that makes sure our input is 16 characters long:

if (sVar2 != 0x10) {

puts("Try Harder");

}

else {

And after that a bunch of bit shifts, additions & multiplications are used before calling check_flag(&local_38);.

/* check_flag(unsigned int*) */

void check_flag(uint *param_1)

{

if ((((*param_1 == 0xcb9f59b7) && (param_1[1] == 0x5b90f617)) && (param_1[2] == 0x20e59633)) &&

(param_1[3] == 0x102fd1da)) {

puts("Good Work!");

return;

}

puts("Try Harder");

return;

}

Assuming our goal is to get to the line that says “Good Work!”, we need to find the correct input to the program that reaches that point. (Perhaps there are more than one due to the bit shifts).

In other words, we have a couple of options:

- Bruteforcing - 16 characters, might be letters, signs, numbers.. too difficult to brute.

- RE - Dynamic/Static analysis, although it’s not fun to reverse ugly code. We can change the value of

param_1at runtime, hooking, etc. - Patching - Patch the program to reach the desired

putscall. But let’s assume that we don’t want to make any changes. - Symbolic Execution (Angr) - Our obvious choice for today. Plus, it yields us an actual valid input to the program.

Angr to the rescue

First, we’ll load the necessary libraries.

import angr

import claripy

Next, we’ll set the base address of the program and load the binary via Angr.

We’ll set the base address of the program, and set “auto_load_libs” to false.

*Note: setting “auto_load_libs” to false will disable CLE’s (Angr’s binary loader) attempt to automatically resolve shared library dependencies. I recommend using it to avoid causing an exception to be thrown whenever a binary has a shared library dependency that cannot be resolved.

# Ghidra loaded the binary to 0x00100000 (default Image Base)

base_addr = 0x00100000

proj = angr.Project('./jack', main_opts={'base_addr': base_addr}, load_options={"auto_load_libs": False})

Filling in the information that we gathered about the binary;

We know that our input needs to be 16 characters long. Therefore, we need to create a symbolic bitvector for our 16 characters. I created a bitvector for each byte in the input, before linking them together.

*Note: a bitvector is essentially just a sequence of bits. A symbolic bitvector is a symbolic variable, which in a sense instead of holding a concrete numerical value, holds a symbol. Then, performing arithmetic operations with that variable will yield a tree of operations (termed an abstract syntax tree or AST, from compiler theory). ASTs can be translated into constraints as seen in the example.

input_length = 16

# claripy.BVS('x', 8) => Create an eight-bit symbolic bitvector "x".

# Creating a symbolic bitvector for each character:

input_chars = [claripy.BVS("char_%d" % i, 8) for i in range(input_length)]

input = claripy.Concat(*input_chars)

Next, getting the entry state of the program while setting the input of the program to stdin.

entry_state = proj.factory.entry_state(args=["./jack"], stdin=input)

Adding a constraint so that each character has to be in the printable ascii range. It’s just an assumption of mine, we don’t know it to be true or false.

for byte in input_chars:

entry_state.solver.add(byte >= 0x20, byte <= 0x7e)

We’re practically done with the setup, and can finally simulate the execution of the binary. In order to do that, we need a SimulationManager, which is a key part here. With it, we can control multiple states, step() & run() similarly to a debugger.

# Establish the simulation with the entry state

simulation = proj.factory.simulation_manager(entry_state)

Now that we can symbolically execute the program, we should set some goals. Where do we want angr to reach, and which paths (branches) we don’t care for.

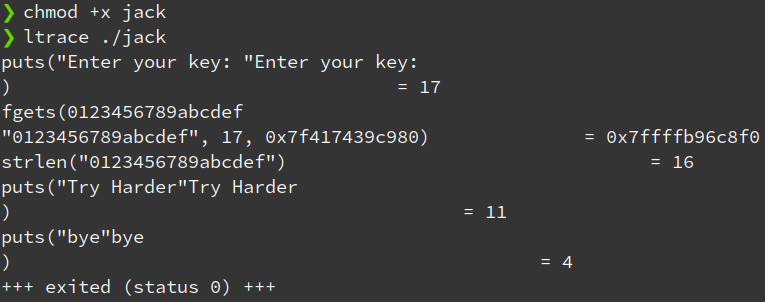

success_addr = 0x00101489 # Address of "puts("Good Work!");"

failure_addr = 0x00101468 # Address of "puts("Try Harder");"

# Finding a state that reaches `success_addr`, while discarding all states that go through `failure_addr`

simulation.explore(find = success_addr, avoid = failure_addr)

*Note: I got the addresses of the relevant puts calls in Ghidra:

Checking if we found a state that reached success_addr is easy:

# If at least one state was found

if len(simulation.found) > 0:

# Take the first one and print what it evaluates to

solution = simulation.found[0]

print(solution.solver.eval(input, cast_to=bytes))

else:

print("[-] no solution found :(")

Executing the script results in a desired input that reaches “Good Work!”

b'n0_5ymb0l1c,3x30'

❯ ./jack

Enter your key:

n0_5ymb0l1c,3x30

Good Work!

bye

Conclusion

Angr can be quite useful in certain cases as shown above. It’s a niche tool, but I think it’s really cool. You can use it as a standalone tool, or with open-source plugins for IDA Pro, Ghidra, Binary Ninja & more.

I hope you’ve enjoyed reading through this blog post. If you want to leave any feedback, you can find my email in the about page.

References

https://docs.angr.io/ - All Angr things

- AngryIDA - IDA Pro plugin

- AngryGhidra - Ghidra plugin

- SENinja - Binary Ninja plugin (similar, Angr inspired)

“Code obfuscation against symbolic execution attacks” - conference paper by Sebastian Banescu. Used part of the definition of “symbolic execution” from this paper.